by Cass Lynch (casspurp)

In-Game Photo Credit: Cass Lynch

Introduction

The trailer for South of Midnight (2025) from Compulsion Games was visually interesting enough to catch my attention: Woodcut art style? Blues soundtrack? Oral Tradition? Was this really an authentic Southern Gothic game?

Pauvre bête. Non.

It’s taken me almost two months to sit down and write this review, despite finishing the game in a mere sixteen hours, because SoM broke my heart.

Note: Quotes were taken from the official documentary unless otherwise noted.

Players were promised a Southern Gothic action game and we were given trauma porn created by (mostly) white Canadian settlers who visited the South once, for two weeks, when they decided to make SoM. In fact, the more you learn about SoM’s production, the more you realize this was one white man’s pet project.

The creative director, Dave Sears, was born and raised in Mississippi, although available online biographies suggest he hasn’t lived in the South since college in 1991. He also has the most screen time in the short behind-the-scenes documentary released online and with pre-order/collector’s edition versions of the game which is ironic considering media and critics hail SoM as a prime example of Black female representation in character design, story, and game development.

Media interviews for the game feature Black developers, but Sears speaks as if employees carried out his instructions or adapted their work to meet his expectations. I found it interesting that Sears only referenced his white colleagues unless he was specifically referencing Hazel, their folklore expert, or musicians–the Black folks that either gave him knowledge or are intellectual property.

I’ll go further and state that I believe Sears brought Black developers on to legitimize his Song of the South and Pristine Myth-inspired vision. Specifically, I believe Sears made this game as a white guilt fantasy that allows non-Black players to feel like they are, as he says, “learning empathy for people who aren’t like [them].” It’s the neoliberal idea that we can solve racism and fix everything by being nice and coddling white feelings because directly referencing slavery or making them feel bad will alienate them as allies.

But I’ll let Dave explain his vision and y’all can judge:

So when I was a kid I spent a lot of my free time, after I had exhausted all the books I wanted to read, exploring sort of all of these abandoned farms and forgotten places, and you really, when you walk through a forest in the South, you never know what you’re going to find. […] [L]ike wild grape vines that were so thick and so gigantic, you didn’t have to climb them. Mysterious buildings and they seemed to have never served any purpose at all, so you wonder, what was this for? Why is this here? Where did these people who built it go? What happened? It doesn’t take too long before the accumulation of mysteries demand an answer, and my imagination provided the answers.

As Sears is talking in the documentary, images of weathered farm houses and historic “ruins” flash on screen as if folks wouldn’t know who’s lived on a given plot of land since it was originally settled. As if farmhouses are indecipherable, mystical pylons. He also calls muscadines, or culoswv, just “grapes” despite his repeated mentions in interviews and their prominence in the environment and character design. The white settler gaze is so strong in this game that I believe actual Southerners, especially former tenant farming families, descendants of formerly-enslaved Africans, and Indigenous folks will feel that familiar sting of transhistorical trauma and exploitation.

And Indigenous and Creole folks–do not expect inclusion in this imaginary South.

We do not exist in the minds of settlers, especially the existence of Southern or mixed Natives. Our ancestors were supposed to have died from disease or marched to Oklahoma on Jackson’s Trails. A few of the stories told in SoM belong to (Afro)Indigenous or Creole peoples, yet the only reference to us is a real place name: Chickasaw County. Natives are like Sears’s inscrutable ruins or mythical cryptids.

But don’t worry! Hazel speaks Spanish… for some reason.

I guess they couldn’t find a French translator in Montreal.

This game feels like a monkey’s paw. We wished for a Southern Gothic game with authentic representation, but it’s controlled by colonizers like Sears who believe, “that it’s important to show the folklore, the magic, and the creatures in the South, and share them with the whole world.” Thanks, Dave.

He frequently uses colonial tropes and loaded language in the documentary, a habit best exemplified in the boast, “That exhilarating sense of discovery, never knowing what you’ll find–this sort of thing is what I wanted to create in a game. The genesis of Midnight was my desire to create a love letter to the South.”

Except he didn’t, really.

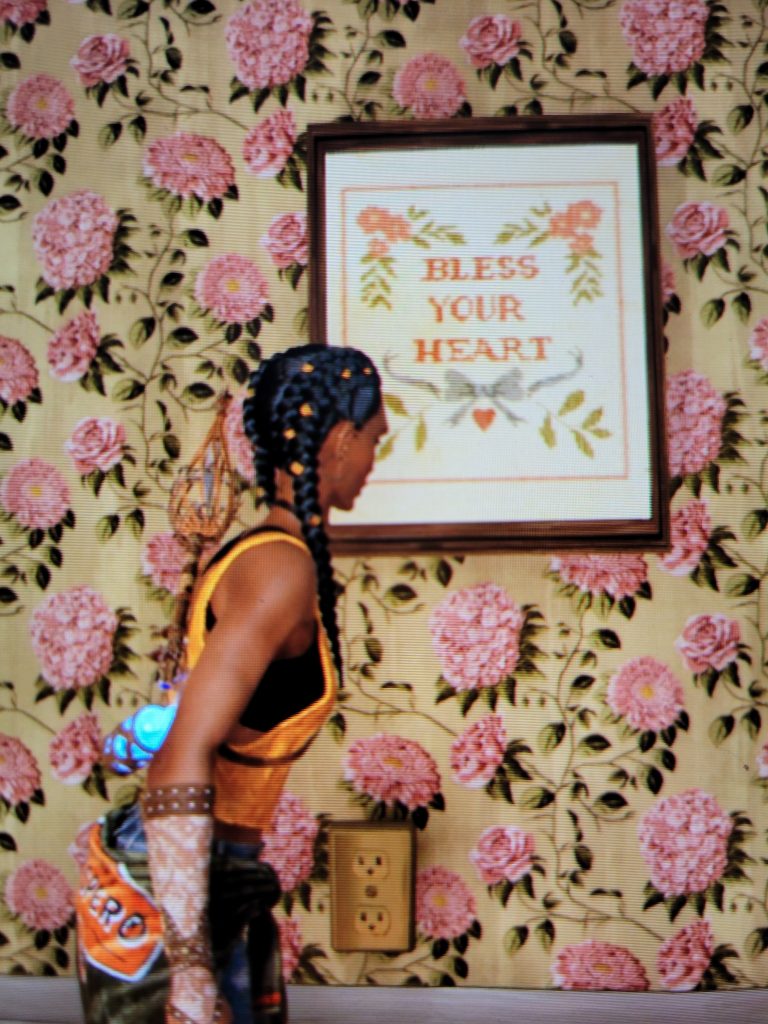

Sears gathered a mostly white team to develop a magical South in which racism is reduced to a personal failing, the antebellum and Jim Crow eras are about family conflict and cannot be referenced by name, and white feelings are appeased. His team emphasizes ad nauseum in media interviews that we are seeing their re-imagined, magical realist Deep South. Whitney Clayton, the white Art Director originally from Vermont, unironically gushed in the documentary, “I feel like we don’t give players enough credit for wanting to see new worlds.” Ouch.

Clayton is the second-most featured developer in the documentary and her speaking manner implies she was the one in charge of bringing Sears’s thoughts to paper. She never directly credits or references the Black artists and unironically revealed the colonial intent of the game to audiences. While images of a plantation house show on-screen, she explains:

There’s a thing [in media] that I like to think about called like an ‘imaginary nostalgia’ for a place, so the idea is that, you know, it’s okay if players have not experienced like where these genres came from originally, but we’re sort of re-imagining them and celebrating them again to create like a really cohesive, atmospheric world. And so for us, how I would have translated that to something visual is really leaning on the weight of the past. That’s the big thing for Southern Gothic: old decaying buildings, overgrowth, quiet places, old houses, places that tell a lot of old stories. And then there’s the supernatural sort of magical realism element with ghosts and myths and legends.

What she’s describing is Imperialist Nostalgia and it’s bad, actually.

To put it briefly, Renato Rosaldo’s theory is that colonizers lament for a “lost” past or “simpler culture” they attempted or successfully destroyed. It’s atavistic and relies on revisionist narratives to control collective memory. What Clayton describes as a positive feature of the game is really one of its most disturbing–a decontextualized, magical South in which Oral Tradition is reduced to ghost/monster stories that unfamiliar (white) players can consume and “beat” or “defeat.”

Which is why I am unsurprised that I have not seen any review mention the game’s failure to refer to slavery and Jim Crow by name, explain what the Underground Railroad was doing and why, how it’s gross that Hazel’s grandma still lives in the Big House, why miscegenation made her white father an outcast, and what it really means for grandma to steal weaving powers from the people her family historically enslaved.

What we get as players is a story of insurmountable grief that drove one white woman to be mean to her family and the mixed Black granddaughter who is charged with fixing the local white folks’s problems and healing their trauma. A few reviews I saw called the game “Black Girl Magic,” as did one of the developers, so I guess that means “…in service to white guilt.” This is a recurring theme throughout SoM which is ironic considering how many detractors cry “woke!” at its mere mention.

Music

Soundtrack composition should be the easiest part of Southern Gothic media production because there are few, if any, regions in the United States with a more established and recognizable sound. Whether it’s the world renowned jazz of Bourbon Street or the Blues unique to the Deltas… the only challenge should be crafting story-specific lyrics or narrowing down a list of music standards.

So what happened?

“We wanted the music to be very much involved… and illustrate the world as much as capturing what the player is doing moment to moment. You know, it goes like ‘bap-bap-bup-bang-bang-bang.’”

— Olivier Deriviere, Composer for South of Midnight

Well, to start they hired a French composer with no cultural connections or musical knowledge of our region who believes classic orchestral music is completely foreign to Southern cultures–despite Ms. Nina Simone telling the world for decades, “‘To most white people, jazz means black and jazz means dirt, and that’s not what I play. I play black classical music.'”

Odd enough, Deriviere used orchestral music as a signal that “evil” is nearby which could have been a great comment on colonialism and racism. Instead, the colonial gaze requires “other” cultures to be simultaneously savage and incompetent so the entity is a scary giant plume of dark, smokey clouds. The inherently-evil “King of Nightmares” is unrecognizable from the Louisiana Cauchemar (Kooshma) spirit which explains why Deriviere perceived the Big Bad as, “completely different and something that is impressive, and that’s why we picked up an orchestra for those moments.”

Each “boss” encounter has a correlating theme, but instead of tapping into the hundreds of pre-existing folk songs or allowing the characters to fully evolve through music, players are patronized with lyrics spelling out each move while summarizing the level they just completed. Songs contain no new information nor do they expand on the history, characters, or conflicts. Each encounter begins, summarizes what’s happening, then ends–and the songs do not connect.

Imagine listening to a white man yell this at you for nearly 10 minutes:

He was my brother, Benjy, his name

He saw things different, he was my shame

And I said goodbye, I said farewell

I took my hammer, my ticket to hell

This chorus describes the character’s actions and motivations, but you don’t learn anything because players have to collect ghostly clues that re-enact moments from the story before the final encounter.

I do not think songs with hard rhyme schemes are juvenile or antiquated like some poets because when it’s done well, you hardly notice the rhyme. But SoM’s themes are 5-minute songs comprising mostly chorus and hard ABAB end rhymes; in other words, they’re damn near unlistenable. And a disjointed score is a bad choice for an Oral Tradition, narrative-driven game meant to evoke deep emotional connections and “empathy.”

Once again it feels like the primary developers gave their teams detailed instructions and only used their Black colleagues as a shield against criticism or a badge of authenticity. The white audio director, Chris Cox, references Black musicians brought on as choir backing or vocal performers, but takes primary credit, “And so we, our writing team and David, supplied those lyrics for these songs.” He continued:

[B]eing able to go to the RCA studio and meet our performers, it’s just historic and I think influences how you make the game, and we wanted to work with these artists from the South, singers from the South, fiddle players, drummers, organ players. David was from a gospel church in Nashville, and the chords and play style is just incredible. Meeting the choir, and everyone’s just got music running through their blood. Amazing to be around, and often left me feeling quite inadequate.

Cox and Clayton are so close to getting the point. So close.

Unfortunately, the songs that are decent or feature Black vocalists still conform to the white colonial gaze and exploit decontextualized historical trauma. I felt the most uncomfortable during Chapter 10, “Light in the Darkness,” which features arguably the most poignant song–a haunting lullaby that carries immeasurable love and grief, but you don’t get it until close to the end-of-game.

We are regularly reminded this isn’t actually the South as Deriviere explains, “[Sears and Cox] didn’t ask me to be like, ‘Okay, do a perfect blues, do a perfect, you know, like bluegrass music, do a perfect country music.’ It was quite the opposite. It was more like, ‘Okay, take the flavor of this, but make it your own. Take it to another land.’”

A New World.

Folklore

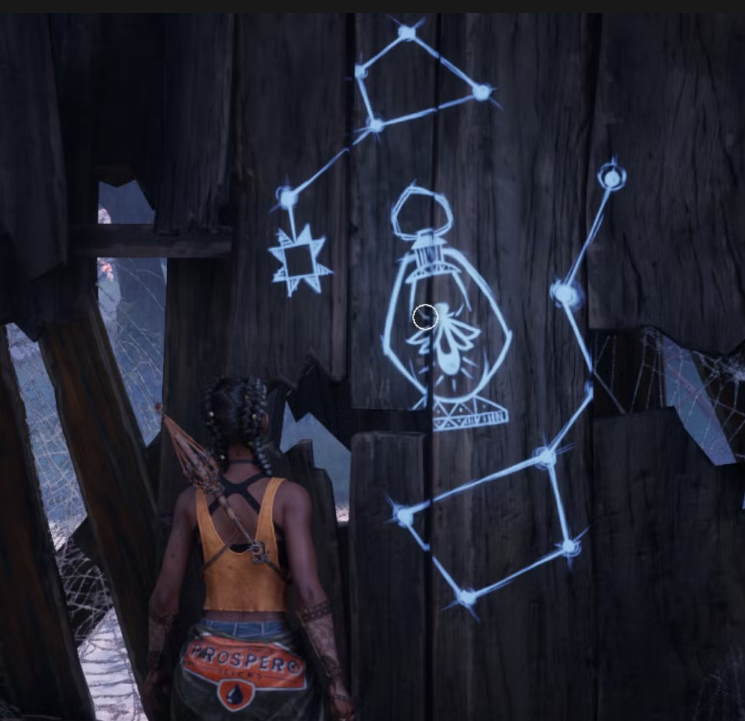

As we search for a way out of the swamp, players meet a childlike plant creature named Honey and play hide-and-seek with him while exploring a wrecked riverboat. We learn his mother, Ayotunde, jumped overboard as the boat neared a rumored Underground Railroad settlement. They survived, but Honey vanished from his hiding spot and Ayotunde slowly morphed into a creature as she searched. The child is later found by Mahalia, the weaver Hazel has followed throughout the game. She cared for the lost baby until he, too transformed into a creature with “leaves for hair, vines for veins, and wild grapes for eyes.”

Altamaha-ha is my people’s story–a Mvskoke story.

But Natives don’t exist in SoM, so Altamaha-ha is not a spirit relative of humans who lives in rivers between Georgia and Florida. Mvskoke peoples are not credited in promotional material because Sears et al. believe the stories belong to “the South” and “Georgia” in the same way settlers believe “Bigfoot” belongs to them.

I don’t know if designers meant for the story to replicate white supremacist myths about African and Indigenous peoples, but it does. The Altamaha-ha and her child are humans mutated by the magical swamp into a TTRPG Naga-like creature and baby Swamp Thing (see: degenerative hypothesis). Then, despite Native absence and the adaptation, the game still manages to pull a Vanishing Indian. After Hazel reunites Honey and his mother, they return to ghost or spirit form and hold hands as they walk into (Christian) Heaven. Rudyard Kipling would be proud.

As Zaire Lanier put bluntly, “Altamaha-ha was just sad as shit;” but the emotional weight of this level is diminished if players do not already know U.S. history or cannot read through the lines. Expository journal entries found around the swamp never use the term slavery, only refer to slave catchers as “hunters,” and don’t explain the historical significance of riverboats or Black women being assaulted by wealthy white men, similar to how some of the haints are just “overseers” or “brutes” without comment.

Lanier’s reasoning for glossing over or omitting context is that a game should appeal to a wide audience and to directly reference the issues would be disrespectful “towards those realities.” Her argument confuses me. Just like our Indigenous ancestors, Hazel’s ancestors would have risked their lives to preserve every bit of culture, language, and spirituality that colonizers were trying to destroy. I believe that presenting watered down or sanitized history only serves the oppressor by further burying the truth and pushing our ancestors back into the shadows. Here’s what Lanier said in full:

“[W]hen you’re writing narrative in a game, you only have so much space to give every story because it’s interactive. For really serious subjects, sometimes that can result in you glossing over something that requires a lot more detail and time put into it. So, trying to walk the line between including these elements and feeling like we were respectful towards those realities while also giving Hazel time to process what she’s seeing because it is traumatic, and applies directly to her and her community. Those were hard to do, but it was rewarding. I think we pulled it off pretty well as a team.”

That last sentence is why I believe Sears and Clayton did not relinquish or delegate creative control as much as the media interviews claim. Sometimes it feels like they’re all reading a script because everyone repeats the exact same answers in interviews, no matter the publication. But I digress…

Lanier and the team’s takeaway for “Light in the Darkness” is that even such a sad story can have a happy ending (or be “bittersweet” as Game Rant said) which undermines any intended historical commentary and further placates white feelings. Compulsion Games, and Sears, emphasize the fantastic nature of their magical South which could be to deter criticism–Honey isn’t dehumanized or a tropic representation of returning to nature… he’s a cute little swamp baby that just wants to play. It’s not that they left out the whole slavery, Jim Crow thing… they just want the game to be appealing to the world and a fun adventure.

I have seen some reviews say the game is great because it includes these stories, but does it? Players will most likely know that chattel slavery was practiced in the South and they might know what the Underground Railroad was, but the game does not make clear the stakes. Developer commentary is confusing because they describe a different game. Does this mean the finished product was condensed or were the interviewees not shown the finalized story?

In the documentary, Dani Dee Bell, the narrative designer said, “A lot of people might hear about the Underground Railroad, but a lot of people don’t know that the Great Dismal Swamp was like a stop on the way. Imagining people built settlements out here is like… really, really wild. It’s very inspirational, though.” I’d argue we still won’t know because the swamp’s significance and the settlements’ origins are never explicitly mentioned in the game, white people are depicted as inhabitants, and Sears et al. keep emphasizing that everything in SoM is fantasy.

Players never have to question the gravity of these events or the power imbalances between the Black characters and their white settler antagonists. We just know some of the characters are sad because people were mean to them or because they are poor (this game is saturated in colorblind racist rhetoric).

Take the story of how the town of Prospero was created.

Players learn that Chickasaw County was flooded in the early 1900s to create the town and families were forced to move after leaving everything behind. Again, the story itself is sad because most people can understand not wanting to lose a home, but we are introduced to a valley filled mostly by impoverished white people who are Tex Avery-level hillbilly caricatures. Despite the game’s focus on class, players don’t learn how these stereotypes were created by capitalists to prevent white “middle class” men from striking in solidarity with their working class counterparts.

The game comes across as settler state propaganda because players are shown nothing but “broken” families and at-risk children being consumed by the swamps or killed by sinful family. Social Services is positioned as a safety net for children and one character calls them on a family which isn’t something you’d see happen in the bayous or Appalachia. Family separation is a plague across the rural South and especially among Black, Indigenous, and poor mining towns; white families also disproportionately adopt Black and Indigenous children.

Yet our protagonist’s mother, Lacey, is a social worker.

There’s a whole extra layer of story where Hazel walks around and sees people being affected, factories that are closed down—basically, the final death throes of a small town. And often in the midst of those death throes, when it’s systemic, when you don’t have money for good public schools, you don’t have resources for public health, sometimes that turns into a lot of hardships within the community. And I think Huggin’ Molly is just the magical folk tale version of a CPS almost. It’s not perfect. Like you mentioned, there are these kids living in the mountains with a giant spider woman, potentially eternally youthful, because [they’re thinking] there is someone out there who is trying to help me and hears me. Because it’s a folktale, sometimes logic doesn’t make 100% sense, but I think folktales are often told as a means to issue a warning or to tell a lesson.

Zaire Lanier, Narrative Designer

There is no mention of Indian Removal opening the southeast for plantations which were later converted to Black sharecropper settlements or resource extraction boomtowns before they were ultimately flooded in the early 20th century to create agribusiness dams. No explanation that the white families in the area would have been given advance notice of the flooding, compensation for enacted eminent domain, and financial help relocating to more desirable property. Were they given lots of money? No, but Black and Indigenous families got nothing and the Klan often burned down homes before the floods.

There’s a voyeuristic quality to the colonial gaze because we are not seeing authentic stories, we are consuming trauma after trauma set to a white man’s idea of Black Southern music. All of the history and stories are filtered through Sears who consumes our cultures for profit. Our stories are conflated, made vague, and reduced to legendary, fictitious “cryptids.” Settlers love our stories, but not our peoples or history. Sears justifies everything by saying stories belong to Southern people, but they don’t. He even admits to intentionally capitalizing on this trend:

Almost all of the creatures within South of Midnight are inspired by folktales from the various regions of the South, and if not a folktale, it’s taken from an urban legend that’s well on its way to becoming a folktale. Something’s out there, clearly, something anomalous. People become obsessed with learning about them, but to date, no one’s really gathered any conclusive evidence or proof that they exist, or really identified what they are.

Western colonizers have told the peoples they colonized that our Oral Traditions are superstitious nonsense since they invented the system. Stories were no longer considered cultural knowledge or history because our ancestors didn’t write things down like colonizers and they weren’t Christian. U.S. education still teaches the lie that “civilization” was invented in the west and “brought” to the rest of the world.

Most people do not know that “medieval” and “enlightenment” era Africa and the Americas were, on average, more technologically advanced and sociopolitically progressive (European colonizers were mocked for their poor hygiene and bad teeth). Instead, most people believe our ancestors were running around naked in forests or shivering in cartoonish huts. Even Lanier seems to believe colonial lies that our respective Oral Traditions were not established literary canons or historical records… just people telling superstitious or funny stories.

She told Deadline, “so much of the storytelling tradition in the South is oral. It’s not like you’ll find a collection of stories unless it’s a Br’er Rabbit-type thing, because there are some established Br’er Rabbit stories. Then you have the more general local legend or folktale….” The Br’er Rabbit stories are not “established” so much as they were appropriated and absorbed into mainstream U.S. culture in an attempt to diminish their significance within Black communities and make it difficult to determine the stories’ origins, thus severing the ties between story and cultural knowledge.

SoM combines colonial insult with Imperialist Nostalgia and appropriation–after all, the stories weren’t good enough on their own; they had to be rewritten and improved. Our cultural figures like Huggin’ Molly need to be further cryptid-ified so they appeal to white players who love Mothman, the Wen—o, Ski—–ers, and Bigfoot (only referred to as such in the southeast by white folks–he’s Skunkape or Altamaha-ha). Sears made it insultingly clear that he, and his team, conducted no substantive research:

None of us were experts in Southern folklore, but we had this monumental task of building a world that was iconic, did feel authentically Southern, and it was with a bunch of creatures that no one in Montreal had ever heard of. I mean, there are a lot of people in the South who haven’t heard of some of these cryptids.

My advice is that if no one on your team is familiar with a subject–pick a new one.

Conclusion

South of Midnight is a visually-captivating game that sells itself as a progressive example of Black video game storytelling, but reinforces harmful stereotypes about Southern cultures while romanticizing the antebellum, Jim Crow, and Hurricane Katrina eras. I do not want anyone to mistake this review as a call for fewer games like SoM or a claim that Black stories cannot be successful–hopefully, you understand my point is that we were all misled by David Sears and Whitney Clayton.

So rather than ending on further negativity, I’m including statements from the Black designers and actors who worked on this project because my criticism should not dissuade anyone from playing this game. We need to support Black creatives and ask for more of their stories in games, but we must also demand transparency and stories told by the actual creatives, not (white) settlers who feel entitled to our cultures. We all deserve better than “hey, at least they tried.”

SoM’s Black Creatives Speak

Adriyan Rae

Voice & Motion Capture Actress for Hazel Flood

“When I first seen a picture of Hazel, I was like, oh, my gosh, that could really be me. Just her facial structure resembled mine.”

“My family’s from North Carolina, so I had a background of what that accent would sound like, and then I had a little bit of training to help me with, just to really precisely place it where it needed to be. And then with her attitude, I just got to make sure I am in a spunky, ready pace. You know, she has sassiness. She has a moderness to her, but she’s also respectful of her elders. She’s also very empathetic. She’s very driven, competitive, and I remember just feeling so connected. Her journey paralleled with my journey and like many of our journeys.”

“So the ability to Weave is you can take these big masses of dark energy and release it from each other, release it so it can — so the good can get in, so the good can thrive. That’s what I love about Hazel Flood, is the things that she’s doing are all a part of healing and helping others.”

“I mean, when I think about how many games are set in the South with a strong black female lead, I don’t recall that many. That in itself shows how important this is.”

“And it’s a journey of finding empathy for those who seem like they shouldn’t receive any at all. I think that’s really important. I think that’s something that makes this game so important and so unique.”

Nona Parker Johnson

Motion Capture Stunt Actress for Hazel Flood

“This story centers around a young black girl, so I couldn’t help but be just in love with that idea, and I think Hazel and the writing and the way that she’s designed, it’s so beautifully powerful, and I think that it just sort of leaps off the screen, and the way that she speaks and carries herself, the way that she allows herself to be vulnerable and scared and confused and unprepared I think is something I’m really excited that we get to follow in this story and her story.”

Zaire Lanier

Writer

“I think it’s really cool that a little black girl could cosplay Hazel with the hair that’s growing out of her head. It’s nice to see yourself reflected in a piece of media and not in a way that feels stereotypical or inauthentic.”

“Games with Black female leads are rare in gaming, especially at the AAA level. I was floored that I was going to be able to work on a project like this. I was excited about it being set in the South with magical realism. I was excited because I was like, ‘Oh, I can represent and write about people I grew up with and have been around my whole life who don’t get represented in these ways in games.’”

We also had movies and books as references. We did Eve’s Bayou, Night of the Hunter, some Zora Neale Hurston, like Their Eyes Were Watching God, and Toni Morrison’s Beloved. Hazel is a conglomeration of a lot of the young Black women in my life, myself included. Like most Black Americans, my family comes from the South. […] One of my biggest inspirations was Spike Lee’s Crooklyn. […] I wanted to capture that same feeling while I was working on Hazel, and her personality and her character journey throughout Midnight. (from Deadline)

Kim Robinson-Mays

Community Manager

“Like Hazel, we can be Weavers. We can be fairies. We can be magic-users. We can do a lot more than just, I think, what people assign to the South.”

Dani Dee Bell

Narrative Designer

“The sort of variety of creatures that we have in South of Midnight is really cool. The creatures and just sort of like the wild embodiment of like nature, but also human anxiety is very interesting, but also like human errors and challenges and the ways that we hurt each other sort of manifest as creatures as well. There’s some sort of whispered rumors about creatures that you shouldn’t cross that Hazel has to.”

“You hope that one day you’ll be able to play a character like that, but it’s really important that Hazel’s story is relatable to a lot of different people. Like, I think you don’t have to also be like a black woman to understand and relate to Hazel.”

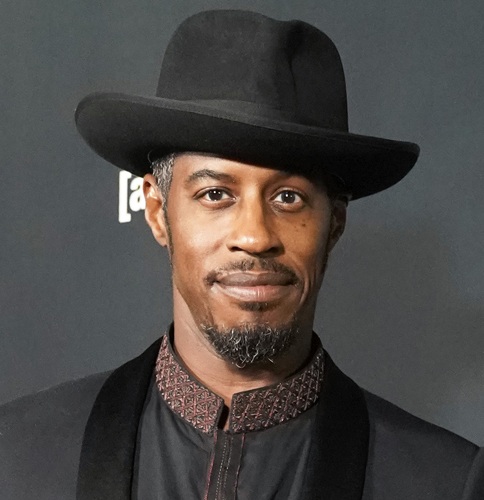

Ahmed Best

Performance & Voice Director

“The challenge is really the fact that a character like Hazel in a game like this hasn’t really been done before, you know, and it hasn’t been done in a way that really brings to light what it is like to be a young black woman in this time period with these challenges and the complexities that come with that.”

“I think it’s just a really strong message that there is a power in healing. You know, we can actually heal through our pain.”